Download a printable copy of this article (PDF 509KB)

Download a printable copy of this article (PDF 509KB)

- Context impacts behaviour.

- We accord our efforts with our feelings.

- Locations play a distinct role in memory and perception.

- Develop small, replicable ways to generate positive feelings.

- Remember that culture is merely a set of repeated behaviours.

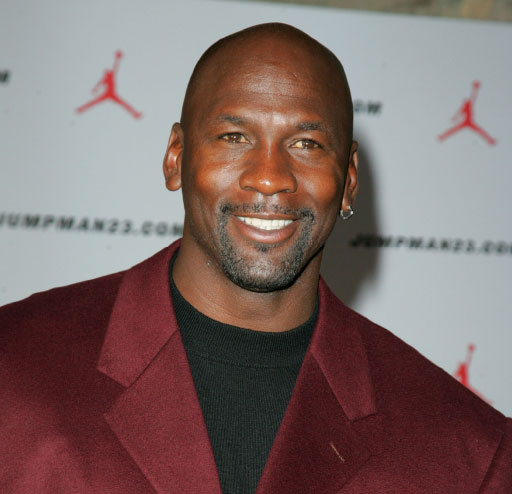

Taking photographs in the Long Room at the famous Lords Cricket Ground is traditionally a no-go action. Hence the expression of disquiet in the photo accompanying this article. I am usually quite uncomfortable with having my photograph taken, but in this case my unease was more geographic than photographic.

Recently, I was presented an amazing and rather surreal opportunity. With a childhood friend, I traversed the planet for the wedding of another old friend. Separated by distance, we’d hardly been in the same place more than a couple of times over the last few decades. Yet, our friendship circle has endured remarkably well. Reuniting was a great old time.

Being in London offered a rare opportunity to lean on my soon-to-be-married friend and his career in cricket. Working with the English cricket team for many years, meant he’d seen all of the English sites that we Australian cricket tragics would consider sacred. It was now or never.

“Be sure you put your feet in theright place, then stand firm.”

– Abraham Lincoln

With a Plan B in place (pretending to be a part of an international physiotherapy consortium) we suited up and walked into the famous pavilion and casually sauntered past the egg and bacon tie wearing security guards.

I’ll never forget the next few steps as we walked up the stairs towards the door to the Long Room. A fog of emotion descended on me. What exactly were the emotions? I think it was an odd blend of humility, privilege, excitement and embarrassment. In some ways, I almost felt I didn’t belong there. But I was certainly grateful that I was.

Now comfortably seated in my very Australian office, I can vividly recall that blend of feelings – far more vividly than I can the actual artworks and details of the place itself. The feeling revisits me when I tell people about our visit. It almost feels as if I’m recounting from the comfort of those brown leather stools. It’s palpable.

It made me think hard about the emotional impact a geographical location can have on people. Renowned body language and message delivery expert Michael Grinder speaks of the contamination of space as something we pay scant regard to in today’s busy life style. Grinder points to the positive and negative emotions that, if generated strongly enough, become the very way we interact with a location.

In schools, these feelings are both generated and regenerated with more regularity than in any other space.

Think about:

- the early years student who routinely starts a tantrum when their parent’s/carer’s car enters the car park in the morning.

- the staff member who is so uncomfortable in the principal’s office that it wouldn’t be possible to conduct a performance conversation there.

- the parent/carer who responds far better to a home pop-in than a sit-down in a meeting room.

- the colleague who seems to unexpectedly either revel in or unravel on school camps.

- the administration officer who goes into meltdown if asked to leave the front desk to help out in a classroom.

The experiences we create and recreate in our schools require some reflection. When was the last time you focused on the feelings you create as priorities to productively enhance future engagement and performance? When was the last time you tweaked or tailored a generic task, such as a performance conversation, so that the context made a positive impact? When was the last time you went out of your way to do nothing other than make a staff member feel happy, valued or special for no other reason than they’d feel good in your school.

It doesn’t take an enormous effort. It can be a random post-it note, a slice of cake or just a kind word. But these small and seemingly innocuous actions can also lead to the establishment of powerful cultural rituals that define us and the places we lead.

In Malaysia, the ritualisation of a simple welcome has evolved into the Salam. Many cultures have these rituals which, like Salam, serve to generate positive feelings. This traditional Malay greeting resembles a simple handshake, but incorporates both hands to initiate the greeting. The two people lightly grasp both hands and then bring both to rest, palms down, on their own chest. The gesture symbolises goodwill and an open heart.

May you generate enough positive feeling to fill your school with positive energy. Perhaps consider developing your own rituals at school so that it is a place where positive feelings and good energy are routinely generated and experienced.